Back انحياز معرفي Arabic বোধগত পক্ষপাতিতা Assamese Когнитивна склонност Bulgarian Biaix cognitiu Catalan Kognitivní zkreslení Czech Kognitive Verzerrung German Kogna biaso Esperanto Sesgo cognitivo Spanish Kognitiivne nihe Estonian Isuri kognitibo Basque

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment.[1] Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.[2][3][4]

While cognitive biases may initially appear to be negative, some are adaptive. They may lead to more effective actions in a given context.[5] Furthermore, allowing cognitive biases enables faster decisions which can be desirable when timeliness is more valuable than accuracy, as illustrated in heuristics.[6] Other cognitive biases are a "by-product" of human processing limitations,[1] resulting from a lack of appropriate mental mechanisms (bounded rationality), the impact of an individual's constitution and biological state (see embodied cognition), or simply from a limited capacity for information processing.[7][8] Research suggests that cognitive biases can make individuals more inclined to endorsing pseudoscientific beliefs by requiring less evidence for claims that confirm their preconceptions. This can potentially distort their perceptions and lead to inaccurate judgments.[9]

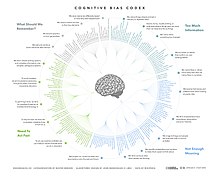

A continually evolving list of cognitive biases has been identified over the last six decades of research on human judgment and decision-making in cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioral economics. The study of cognitive biases has practical implications for areas including clinical judgment, entrepreneurship, finance, and management.[10][11]

- ^ a b Haselton MG, Nettle D, Andrews PW (2005). "The evolution of cognitive bias.". In Buss DM (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 724–746.

- ^ Kahneman D, Tversky A (1972). "Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness" (PDF). Cognitive Psychology. 3 (3): 430–454. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(72)90016-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- ^ Baron J (2007). Thinking and Deciding (4th ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Ariely D (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-135323-9.

- ^ For instance: Gigerenzer G, Goldstein DG (October 1996). "Reasoning the fast and frugal way: models of bounded rationality" (PDF). Psychological Review. 103 (4): 650–69. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.174.4404. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.650. hdl:21.11116/0000-0000-B771-2. PMID 8888650.

- ^ Tversky A, Kahneman D (September 1974). "Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases". Science. 185 (4157): 1124–31. Bibcode:1974Sci...185.1124T. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. PMID 17835457. S2CID 143452957.

- ^ Bless H, Fiedler K, Strack F (2004). Social cognition: How individuals construct social reality. Hove and New York: Psychology Press.

- ^ Morewedge CK, Kahneman D (October 2010). "Associative processes in intuitive judgment". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 14 (10): 435–40. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.07.004. PMC 5378157. PMID 20696611.

- ^ Rodríguez-Ferreiro, Javier; Barberia, Itxaso (2021-12-21). "Believers in pseudoscience present lower evidential criteria". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 24352. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-03816-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8692588. PMID 34934119.

- ^ Kahneman D, Tversky A (July 1996). "On the reality of cognitive illusions" (PDF). Psychological Review. 103 (3): 582–91, discussion 592–6. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.174.5117. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.3.582. PMID 8759048.

- ^ Zhang SX, Cueto J (2015). "The Study of Bias in Entrepreneurship". Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 41 (3): 419–454. doi:10.1111/etap.12212. S2CID 146617323.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search